Not Your Father's Oil Shock

The sensitivity of the US to oil shocks has come down a lot as the US has shifted to a net oil exporter and reduced the share of spending on oil. It'd take Brent closer to $100 to cause real concern.

The US economy is far less sensitive to an oil shock than in previous decades. While the ongoing Mideast conflict is a concern, it would take multiples of the the impact priced in so far to have meaningful economic impact.

Oil price shocks are a pretty common and mechanical in their impact, so their impacts can be understood pretty easily. Drags from rising oil prices come from higher spending on oil by HH & biz as prices rise both directly and indirectly.

In addition the higher inflation readings often will cause a central bank to be tighter relative to what policy would have been otherwise, as the inflation concern is usually a greater concern than weakening growth.

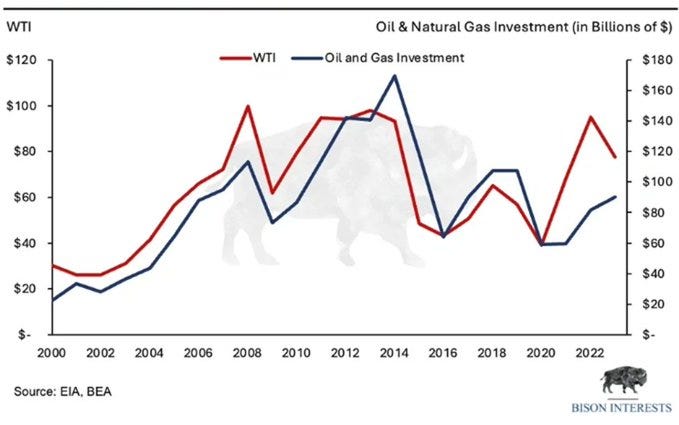

That is offset in part by increased income from oil producers and any rise from investment that comes from higher oil prices incentivizing greater production efforts. This depends a lot on the size of the oil production of the country.

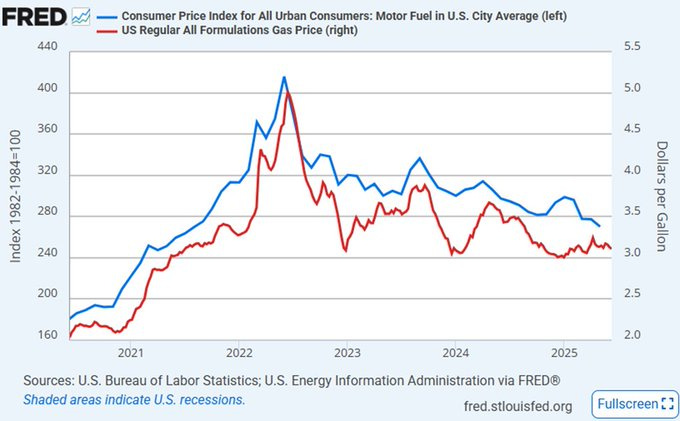

So far the moves have been pretty small in any context even of recent moves. Brent is up about 5 bucks and traded gasoline prices up a dime with it since the conflict started. Overall we’ve seen about a 15% rise since the recent bottom.

Given the recent moves and the typical lags we are likely to see roughly 10% rise in consumer gasoline prices in coming weeks. While the relationship with CPI is loose at best, that's enough to add a couple tenths to annual headline numbers.

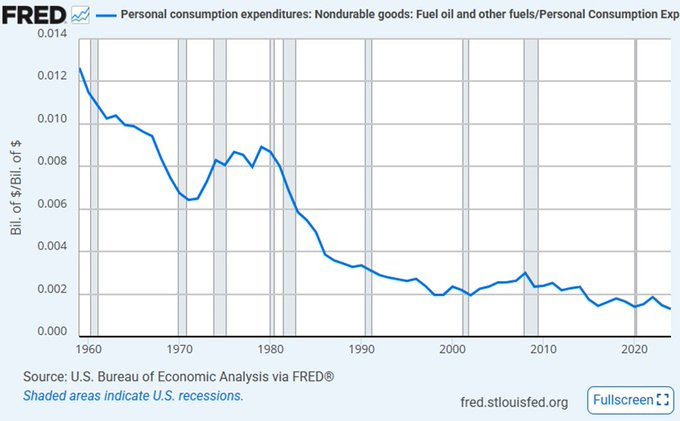

But oil shocks these days have a much more muted impact on household spending than those of the past. Spending on fuel has fallen to a mere 1.3% of overall household consumption, with the moves so far likely not noticeable (say vs. tariffs).

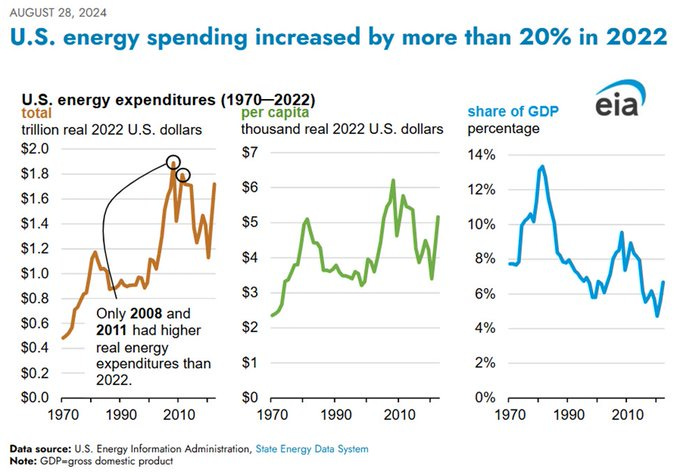

The story on an economy wide level is also the same - much lower than in the past. Even with the peak at $5 gas in ‘22, US *total* energy spending was only 6% of GDP, with non-electricity petroleum consumption a little over half.

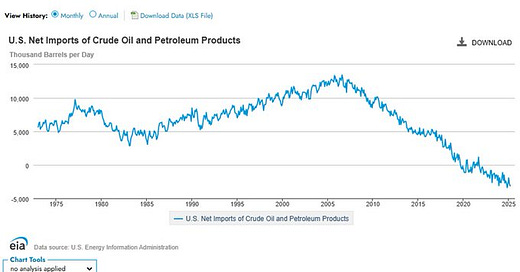

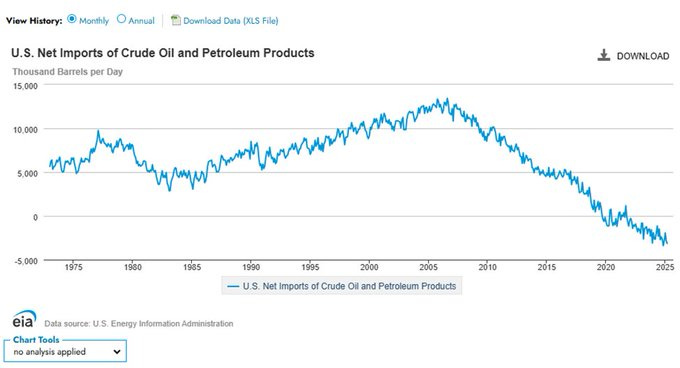

The surge in US production of oil has made the US sensitivity to an oil shock very different today from in the past. At this point the US is now a net *exporter* of crude products, which highlights the domestic income boost from higher prices.

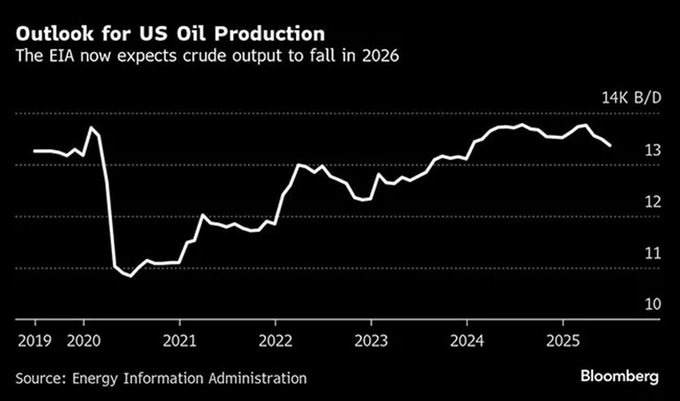

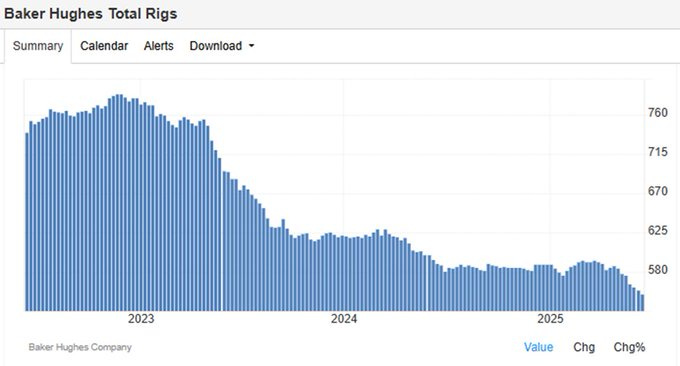

The recent price rise is notable in the context of recent flagging production as a result of lower oil prices. Higher prices are likely to help stem this recent slowing.

Which had become somewhat acute recently. Higher prices should help make what had looked like marginal production profitable enough to turn on.

And with it incentivize a stabilization in ongoing oil investment relative to what would have occurred which at this point now totals a volatile sector of around 0.5% of GDP.

As for monetary policy shifts, the surge in oil prices lifted 2s about 5bps, hardly noticeable in the context of the overall volatility of monetary policy expectations.

The surge in US production to the point where the US is a net exporter highlights how an oil shock may not be nearly as detrimental as in past rounds. While it would create a drag on HH consumption and rising inflation, it will also support domestic production & investment.

As the Fed meets, the possible impact of these tensions on domestic prices & the economy are will be discussed. While the impact is modest even with a more significant price rises, it'll probably be noted as another reason to "Do Nothing for Longer" for a Fed inclined to do so.